- character, face, representation -

In '20-ies Lev Kuleshov shot a single long closeup of an actor named Mozhukhin, sitting still without expression. He then intercut it with various shots, which comprised a bowl of soup, a woman in a coffin, and a child with a toy bear. The audience "marveled at the sensitivity of the actor's range."

In 1961, by looking at his face during the trial in Jerusalem, Hannah Arendt points out that Eichmann was a mild mannered civil servant with a wife and kids who epitomized the virtues of the German middle class. It was in his dispassionate face that Arendt saw “the banality of evil”.

In Shoah (1985), Lanzmann’s nine-and-a-half-hour filmic meditation on memory, testimony and annihilation, there are only images of faces and places: interviews with survivors, perpetrators and bystanders intercut with present-day footage of the killing sites.

What is particularly disconcerting about a number of the survivors’ expressions, is their habitually impregnable impassivity. The camera repeatedly lingers on these faces, inviting us to scan them for insights into the past and the present, yet even when the witnesses are remembering the most excruciating suffering, their faces often remain inexpressive, deadpan, at once unreadable and available to a multiplicity of readings.

Shoah strips the face of spectacular qualities and re-maps it instead as a trauma site. In the absence of direct images of the past, the survivor’s face becomes the place not only where trauma is visually registered but also where the interdiction on representation is affirmed. In this way, the visible face incessantly points to or signifies something beyond the visible, something that perpetually eludes our vision and escapes our knowledge and understanding.

For Levinas, the human is not represented by the face. Rather, the human is indirectly affirmed in that very disjunction that makes representation impossible, and this disjunction is conveyed in the impossible representation.

"There is first the very uprightness of the face, its upright exposure, without defense. The skin of the face is that which stays most naked, most destitute. It is the most naked, though with a decent nudity.... The face is meaning all by itself...it leads you beyond."

"To my mind the Infinite comes in the signifyingness of the face. The face signifies the Infinite.... When in the presence of the Other, I say, “Here I am!”, this “Here I am!” is the place through which the Infinite enters into language.... The subject who says “Here I am!” testifies to the Infinite." (Emanuel Levinas)

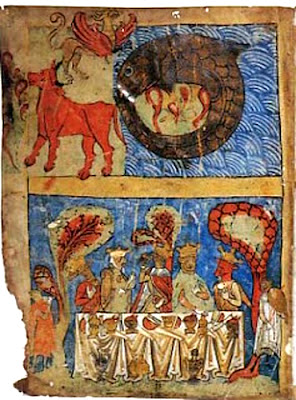

In "The Open" (2002) Agamben analyses images from 13th century Hebrew bible in which the righteous are presented not with human heads, but with those of animals.

For Agamben, “the righteous with animal heads…do not represent a new declension of the man-animal relation,” but instead indicates a zone of non-knowledge that allows them to be outside of being, “saved precisely in their being unstable”

against representation

If humanity allows itself to venture into the pure realm of things beyond representation, then it may be capable of embracing its true vocation beyond vocation. The moment we fully embrace this realm beyond all representation, the moment we dissolve transcendence and therefore immanence as well, is the moment we embrace a materialism beyond the animal-human or human-divine dichotomies, a materialism that can only as such be - divine.